Today marks the four-month anniversary of my Love’s death.

I cannot believe it’s been 123 days, and yet I also feel I have lived and died several lifetimes within that period.

What follows is a glimpse into my journey through loss.

The accompanying score, “Forgotten Keys,” was composed by Michael in late 2016. This draft was exported on New Year’s Day 2017. Many of you will recognize it as the score for Tess Lawrie’s reading of Mistakes Were NOT Made: An Anthem for Justice. This is the complete version and contains an additional two-and-a-half minutes previously only heard by Michael and me.

The Art of Losing

“It’s so curious: one can resist tears and ‘behave’ very well in the hardest hours of grief. But then someone makes you a friendly sign behind a window, or one notices that a flower that was in bud only yesterday has suddenly blossomed, or a letter slips from a drawer … and everything collapses.”

—Gabrielle Colette

“Look on each day that comes as a challenge, as a test of courage. The pain will come in waves, some days worse than others, for no apparent reason. Accept the pain. Little by little, you will find new strength, new vision, born of the very pain and loneliness which seem, at first, impossible to master.”

—Daphne du Maurier

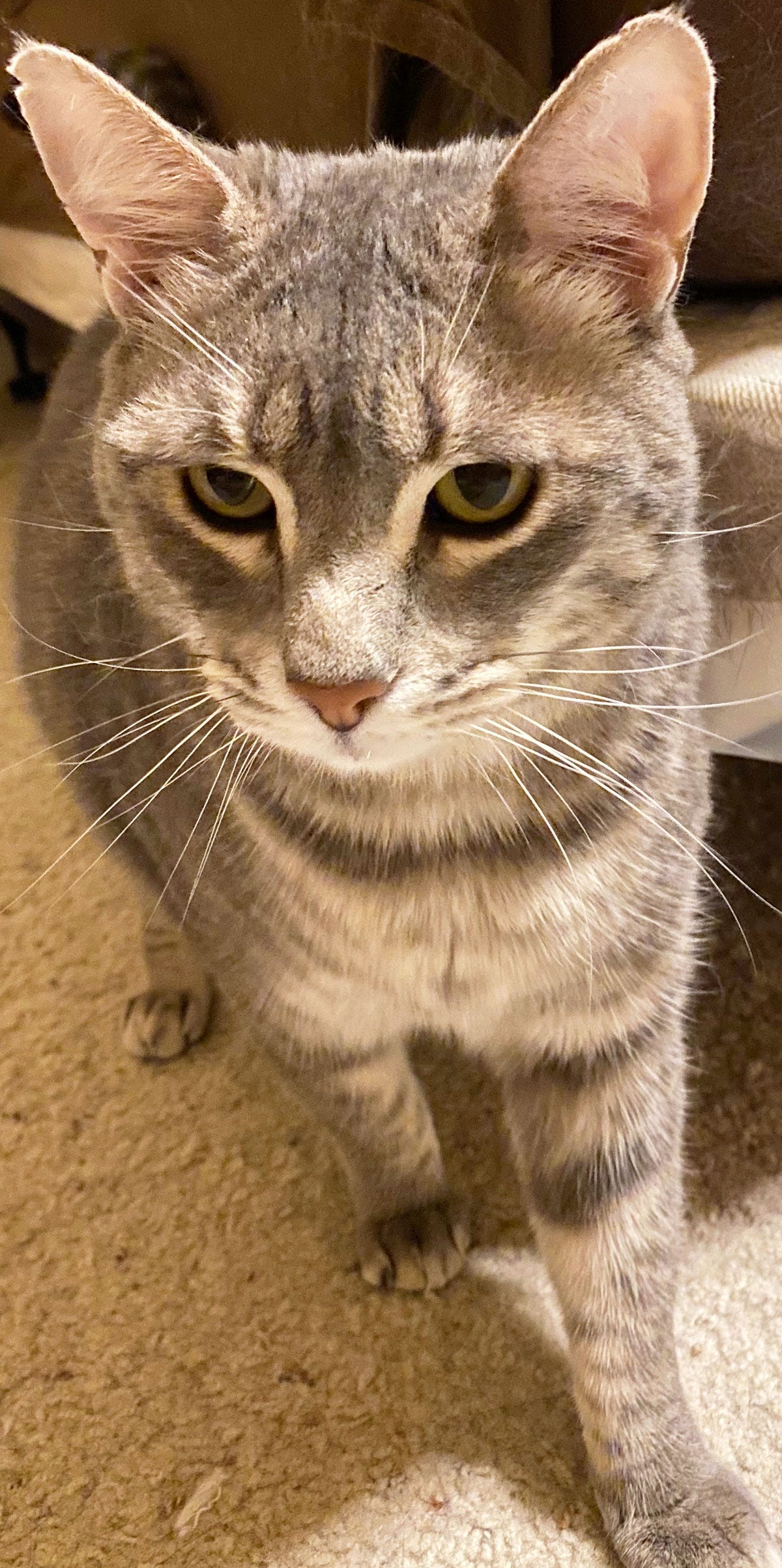

I lost Brownie one morning. I knew something was wrong when she didn’t come out to eat.

Our petite, cutiepie tabby Brownie had seemingly vanished from the house. I tore it apart trying to find her, calling her frantically for forty minutes.

I even sat on the chair behind my standing workstation where I go when kitties want lap time and scooted it forward while calling “Brownie!” which almost always brings her leaping to my lap within seconds. I draped the Brownie blankie—a small gray weighted blanket Michael got to protect my thighs from the pinpricks she imprints all over me while making brownies—across my legs and called her again. Nothing.

I got out her favorite fishing pole toy with the bell and started ringing it. No response.

I looked everywhere I thought she could possibly be multiple times. I started to worry she had gotten out of the house, but I couldn’t figure out how because all the windows were closed, and I am always obsessively careful when I open doors.

I began to despair, terrified she had died and I would only find her once the odor alerted me. Worse, she might be stuck somewhere and then die of starvation because I had failed to find her.

Whenever we lost something—keys, phone, glasses, a kitty—Michael was almost always the one to find them. I would search and search and search, exhausting seemingly every possibility. Then I would ask Michael to look, and he would find it in seconds.

This was yet another example of something I had relied on Michael for that I now had to resolve myself. I couldn’t give up. Brownie’s life was at stake.

The only other place I thought she could be was behind the washer and dryer, but we had previously blocked off access to it with padding and cushions because we didn’t like them hiding in an inaccessible spot.

After the emergency personnel poured into the house the morning of Michael’s heart attack, the kitties tore out the padding and squirreled their way back there. I later reinforced the blocks, so I assumed she couldn’t be there.

Now I realized it was the only place left to look. I ripped away the stuffing and climbed on top of the washer, peering into the crevice between the washer and the wall.

There, cuddling with our orange fluffy girl, Sunny, was little Brownie gazing up at me. Terrified by my Tasmanian devil ransacking of the house, Sunny had joined Brownie in her hideaway.

I yanked the rest of the padding out to clear a path for their exit. Brownie had hopped down through a gap above the dryer but got stuck because the passageway between the washer and dryer was obstructed.

Sunny dashed out, but Brownie wouldn’t budge. I tried food, treats, the fishing pole toy, scooting on my chair—nada.

I went back to check, and she was no longer behind the washer—or anywhere else I looked! I had lost her again!

I scooted my chair and called, “Brownie! Broowwwnnie!”

A few moments later, she tip-pawed up beside me, eyeing me nervously before hopping onto my lap.

I scrunched and cuddled and hugged and kissed my darling Brownie, feeling as if she had been resurrected.

Amazing grace! How sweet the sound

That saved a cat like her!

She once was lost, but now is found;

Was gone, but now is here.

I wept with joyous relief and gratitude for prayers answered.

Yet my elation was tinged with the bitter realization that no such physical reunion would be occurring with Michael—aside from the luminous dreams where I get to see and talk with and hug and laugh with him again.

The anguish of having lost him will remain carved into my viscera for the rest of my life.

I am longer simply me; I am me minus Michael.

I will always feel the cutting presence of his absence, captured in these lines I jotted down at different intervals after his passing:

the noises I think are you

the salty scent of your sweat embedded in your T-shirts,

the last carafe of pseudo-sodey you mixed up,

strawberry-hued from carbless syrups—

I left it on the sink until mold grew on the surface,

finally pouring it down the drain ten days later

the indentation in your recliner

cloaked in your purple blanket, your winding sheet

the last images of you, stills from when you replaced

the security camera at 3:24 am your final morningan itch that can’t be scratched

a gouge that can’t be patched

an ache that won’t go away

a silence where your voice should be

Listening to the audiobook of Oliver Sacks1’s newly released Letters, I was struck by the similarity of his description of grief following the loss of his mother:

“In a sort of way, perhaps, one takes people for granted when they are around, and one feels the intensity and the detail of their presence only when they are gone or taken away: certainly the sense of the absence of Ma’s presence was overwhelming at first—I constantly dreamt of her (particularly a tormenting dream that she had been taken ill in Israel, but fortunately made a complete recovery), and thought I heard her voice, and constantly expected to see her in the lounge or the breakfast-room; I am sure one’s deepest and most elemental perceptions are perceptions of presence (and of its changes, or of its vanishing).”

Whenever Michael and I watched a movie for the first time that was to become a favorite, there was usually a scene where we each felt our hairs stand on end, and a swift meeting of the eyes would confirm we were both feeling it and knew this was special.

In Still Life, that moment occurred when the protagonist—a council worker (of whom Michael said through tears as the credits rolled, “He’s lovely”) charged with finding the relatives of those who died alone—notices three finger swipes in a jar of cold cream he found on the vanity of a dead woman.

Like those finger swipes, nearly every object in our home testifies to Michael’s absent presence.

Oliver’s mother died exactly the same way Michael did. In a January 12, 1973, letter to Richard Lindenbaum, Oliver writes:

“My mother died suddenly on November 13—an instantly-fatal coronary, without premonitory symptoms.… The terror and solitude of the abruption was appalling … absolutely I felt as if the foundation of my own world had utterly vanished.”

I often feel like Wile E. Coyote after zooming off a cliff, suspended in mid-air until I realize there’s nothing beneath my feet and I splat onto the canyon floor.

I sometimes come unstuck in time like Vonnegut’s Billy Pilgrim.

I’m caught in a Rosemary’s Baby loop, repeatedly rediscovering, “This is no dream! This is really happening!”

Just as our cats keened the evening of Michael’s departure, so did Butch, Oliver’s mother’s dog:

“Our dog, my mother’s dog, Butch, who had been away (as usual) at the kennels, came back the weekend after the Shiva, seemed to throw an instant all-seeing glance around him, and then (unprecedently) burst into a loud, terrible canine howling, and then after some hours, sank down motionless, and then ceased to eat. […] Absolutely, without a doubt, that dumb loving beast perceived in a moment the taking-away, the permanent gone-ness of Ma’s loved presence, and at once became sick with loss and grief.”

For over three-and-a-half months, our cat Rusty avoided sleeping on Michael’s chair, where he had previously spent his days glued to Michael’s lap doing undercover work as a sleeper agent.

Then a couple weeks ago, I found Rusty curled up on the purple blanket on Michael’s chair. He has been sleeping there daily ever since. It’s like he had been waiting for Michael to come back the entire time, and Rusty finally understood he was never going to return.

I, too, have had to make peace with that world-shattering awareness.

Four months into this long night’s journey into day, I find myself questioning at moments, How am I even functioning?

The wailings are less violent and frequent now. I no longer walk around feeling like an overfilled mug, ready to spill at the gentlest jiggle.

I keep wondering if there is going to come a day when I don’t cry. And then I wonder if I will feel guilty when that day does eventually come. Maybe I’ll get through a whole day and realize I haven’t cried. And then another day.

I’ll probably feel like I’m betraying Michael, but then I’ll remember that’s what he would want for me. He wouldn’t want me to suffer. He would want me to bounce back and keep fighting, which is what I’ve done, what I’m trying to do.

One of the characteristics that made Michael fall in love with me is my apparent indestructibility.

I am genetically clumsy, so I was always bumping into furniture, banging my head on cupboard doors, or bruising myself on the corners of tables. Instead of crying or dwelling on the pain, I would just laugh it off and keep doing whatever it was I was doing that had made me oblivious to my physical surroundings and even my own physicality.

Similarly, I didn’t dissolve into self-pity if someone did or said something mean to me. Yes, it would hurt; it might even leave an emotional bruise, but I would use it as an opportunity for growth and deeper understanding.

I remember Michael telling me long ago to let insults roll off me like water off a duck. Decades before we studied Stoicism, he was teaching me its tenets.

Having been reared in a landscape of grief after losing his mother and later his grandmother, Michael feared getting too close to anyone, lest he lose them and his heart get battered all over again.

My resilience made him trust I would be able to withstand whatever life threw at me, so loving me wasn’t quite so dangerous.

A few weeks after he died, I was sawing through a fallen tree limb to make it fit into the yard debris bin when I realized I’m going to have to become even stronger now—not only emotionally, mentally, and psychologically but also physically.

Walking to the mailbox by myself for the first time—we’d always walked there together, holding hands—I remembered what he taught me about situational awareness. I lifted my eyes from the ground; stared boldly ahead; and took long, confident strides so I wouldn’t look like a victim.

When I am faced with a technical challenge or physical puzzle, I ask myself, What would Michael do?

Research it. Read the manual. Watch video tutorials. Read articles. Search forums. Take it apart. Put it back together. Bricolage it.

Every time I accomplish something I would have asked Michael to handle, I think, “Michael would be so proud!” While telling my mom this, I found out she was doing the same thing after she tackled home repair challenges.

I started making a list of things I would have told Michael:

“Cloudy left this ginormous mat on the bathroom floor! It was like she wanted to make sure I saw her gift, knowing it would cheer me up.”

“Did you notice how in The Accidental Tourist Macon Leary designs a body bag to sleep in to minimize his laundry, but, of course, that’s a perfect metaphor for his self-cocooning to avoid having to experience the pain of life, love, and ultimately loss? This was one of the few details from the book that wasn’t meticulously captured in the film, an otherwise near-perfect replica. Here’s the passage:

“‘He had developed a system that enabled him to sleep in clean sheets every night without the trouble of bed changing. He’d been proposing the system to Sarah for years, but she was so set in her ways. What he did was strip the mattress of all linens, replacing them with a giant sort of envelope made from one of the seven sheets he had folded and stitched together on the sewing machine. He thought of this invention as a Macon Leary Body Bag. A body bag required no tucking in, was unmussable, easily changeable, and the perfect weight for summer nights. In winter he would have to devise something warmer, but he couldn’t think of winter yet. He was barely making it from one day to the next as it was.’”

“Did you ever catch the language play in North by Northwest when Eve Kendall asks Roger O. Thornhill, ‘What does the ‘O’ stand for?,’ and he says, ‘Nothing’?”

“While watching this clip of scenes from Big Night as I was composing How to Build a Joyful Marriage, it occurred to me that the reference to Willa Cather’s O Pioneers! (“families on the trail”) alludes to the fact that Primo and Secondo are pioneers of genuine Italian cuisine in the American restaurant scene, which is not ready for such sophisticated fare—much as the Hollywoodized American public was not ready for nuanced independent film at the time Big Night was released. We’ve probably talked about that before, but it came into sharper focus while I was watching that montage.”

I quickly abandoned this practice as I found I would almost constantly be annotating my life instead of living it, a habit Michael cautioned me against that had earned me the moniker The Recorder.

Whereas I try to save everything I find meaningful—as is evident from the thousands of date-stamped quotes I recorded by Michael over the years—he didn’t expend energy storing things away.

On April 10, 2008, he told me:

“You and I are very different. You can’t let go of things; I don’t even grab ahold of them.”

He felt that while you’re focused on capturing an experience, you are outside it and cannot be present within it.

He was always trying to teach me to BE with the ones you love … while you still can.

We were accustomed to sharing everything we thought, read, saw, watched, or heard that we knew would be of interest to the other. If the other was sleeping, we’d save them up like treasures to present later.

“It isn’t much good having anything exciting, if you can’t share it with somebody.”

—Pooh, Winnie the Pooh

“We didn’t realize we were making memories. We just knew we were having fun.”

—also Pooh

That was our life together. I never noticed how much laughter filled our days until the days went mute.

I used to rarely think about the past because I am vigilantly focused on the present, but the past is where I find Michael now. He was the keeper of my memories for that reason, and I am left wading through musty and faded photographs, struggling to color in the missing hues before they crumble to dust.

Previously a consummate pragmatist, I now understand sentimentality. I understand why objects held so much meaning for Michael, as if the humans who once touched them could still be sensed, like an iridescent oil slick on a pothole puddle.

Michael didn’t cry about his grandmother, who died when he was nine, until he found her red dress in his grandparents’ closet. He pulled it out and laid it on the bed, clinging to her dress as he wept all the tears that had been trapped inside.

I am now ashamed of how callous my pragmatism made me at times. Once, while searching for a gift for a friend fluent in French, I contemplated giving him the French translation of Catcher in the Rye Michael had hunted down to give me for my birthday several years prior. I was being practical—here was someone who would be able to appreciate it more than me since my French was so rouillé.

Michael was clearly hurt. I immediately jettisoned the idea, but the thought that it even occurred to me horrifies me. I feel myself writhing with regret, wrenching my fingers into the sand like Zampanò at the end of La Strada:

Numerous veterans of loss have warned me grief is nonlinear. Just when I think I’ve turned a corner, something happens to reopen the wounds, and they start gushing as if they were fresh.

Two weeks ago, our outdoor cat Secondo developed an upper respiratory infection (URI). He stopped eating and drinking. With each passing day, he grew weaker.

I kept presenting him with plates featuring smorgasbords of his favorite wet foods, dry food, treats, low-sodium tuna, and high-calorie nutrition paste. He wouldn’t touch any of it.

Accustomed to finding him waiting on the patio, peering through the sliding glass door, or on the feeding table, I felt my stomach sink every time I looked out and didn’t see him.

Even more distressing was when I would search the yard for him and couldn’t find him.

Originally feral, Secondo had been diagnosed as FIV+ when we got him fixed in 2018. Our vet gave us the option of making him an indoor kitty or euthanizing him. She said his immune system was compromised, and it would be dangerous for him to remain outdoors. She worried about his infecting other kitties, too. (I later learned from Alley Cat Allies it is highly unlikely a neutered male (or any female) would transmit FIV because transmission only occurs with deep bite wounds. FIV+ kitties can live normal, healthy lives, especially if they’re indoors, so please don’t ever kill them.)

That’s when we set him up in our bedroom, which became his sanctuary. For the first two months, he hid under the bed.

I would put his plate of food under the bed, inching it closer to the edge over time. I started lying down on my side while he was eating so he wouldn’t feel threatened by me.

Eventually, he started coming out from under the bed to eat. I switched from lying down to sitting cross-legged on the floor, and I positioned his plate in front of me.

When I stretched out my hand to pet him, he retreated. So I bowed my head to him instead. After enough times of my doing this, Secondo head-butted me. That was the beginning of our cuddle sessions, during which he would love-bomb me, rubbing my head, face, knees, and hands as he circled me dozens of times at each encounter, sometimes for as long as half an hour before eating.

He spent nearly five blissful years without illness in the bedroom. Then, one day, he accidentally tore the window screen and fell outside. One of our outdoor kitties, Lovebug, chased him out of the yard along with his best friend and the neighbor’s kitty, Mouser. They understandably thought he was an intruder.

Secondo disappeared. I called and searched everywhere for him, posted to the neighborhood group, and followed all of the usual tips for finding lost cats. I was reliving my nightmare of his brother, Primo, going missing in 2018, which left a wound in my heart that has never healed.

Six weeks later, Secondo showed up on our front-door security camera. I started putting food out there, and he began sleeping on the doormat. After a few months, he migrated to the back yard, where he had lived before he became an indoor kitty.

And that’s where he’s been living ever since, having reverted to his feral ways in that I can no longer touch him or get within a few feet of him.

So when he got sick, I couldn’t pick him up. I couldn’t get near him. I couldn’t administer medicine in his food, not that there is any medicine to heal URIs. I couldn’t even lure him into a humane trap with food so I could bring him inside or to the vet.

I just had to keep offering everything I could conceive of, placing plates in the yard near where he was sleeping. If I tried to get too close, he would run away.

I felt helpless to help him.

As each day without food passed, I grew increasingly anxious. I kept waking up in the middle of my sleep to search for him and put food out.

I feared I would discover him dead in the bushes—or worse, I wouldn’t find his body until much later, if at all.

One morning after I’d woken up in the middle of my sleep to search for Secondo and leave food out, I returned to bed distraught. It had been nearly twenty-four hours since I last saw him. I wasn’t sure how much longer he could survive without food and water.

I wailed and sobbed and wept and wailed some more. I grieved Michael afresh again and lamented that I could not endure another loss, begging for a reprieve.

My eye pillow became so saturated with tears, I had to turn it over. After exhausting myself crying, I fell asleep.

When I awoke a few hours later, I rushed out to search the yard, bracing for the worst. Then my eyes alighted on his beautiful, green, still-alive eyes.

I raced inside to make up a plate of tuna, wet food, and dry food for him. I set the plate down in the grass and talked to him soothingly for a few minutes. He relaxed but still didn’t show any interest in the food.

Then, that evening, I texted my mom:

“Secondo just came to the patio and ate a few bites of the food I left out for him, and then he scratched the wood like he is feeling better!!!”

That’s when I knew he would survive. Just as I had with Brownie, I felt a sense of resurrection.

I experienced this with Michael once, too.

After enduring three days of tormenting pain before relenting and driving himself to the hospital in 2008, Michael underwent emergency gall bladder surgery for a life-threatening infection.

I remember perching in the waiting room during the three-hour surgery, scribbling in a notebook at the speed of thought as I poured out my anxieties, fear of losing him, and desperate pleas that his life be spared.

And it was. We got sixteen years of bonus life before the grace period ran out, every day an exquisite gift.

The phrase “recalled to life” keeps replaying in my mind. In Letters, Oliver’s inveterate editor, Kate Edgar, writes in a footnote:

“OS often referred to Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities, a favorite book from his childhood. The first part of the book, about Dr. Manette’s release from the Bastille, is titled ‘Recalled to Life.’”

It struck me that in addition to the obvious meaning of resurrection and redemption, “recalled to life” could also mean remembering someone back to life. In other words, it is by cherishing our memories of our lost beloveds that we imbue them with another sort of life.

As I was struggling to decide what to inscribe on Michael’s marker that would fit within the twenty-two allotted characters, I flipped through the James Trapp translation of the Tao Te Ching we’d bought two months before Michael’s death.

The book fell open to Chapter 27, where I read the lines:

Thus the Wise Man excels in the care of his people

And no-one is ever lost to him

He excels in the care of his possessions

And nothing is ever lost to him

And there was the inscription I felt Michael had guided me to:

“No-one is ever lost.”

In the document where Michael had been collecting translations of the Tao Te Ching, Chapter 27 was still highlighted in most of the translations, likely because he had been copying them over to a database and had left off on that chapter.

Over the years, we had suffered many losses—not only of loved ones but also of digital artworks, music, and documentary work due to corrupted hard drives or operating system failures.

I still grieve those data losses—even more so now because they are precious artifacts of our creative life together, and it is these remnants that enable me to recall him to life.

But Michael was always unfazed by such vanishings, knowing they served their purpose in the moment and trusting nothing—and no-one—is ever lost.

In a December 30, 1978, letter to his dying Aunt Len, Oliver wrote:

“You, who have always loved life, and been such a source of strength and life to so many, can face death, even choose it, with serenity and courage, mixed, of course, with the grief of all passing. We, I, can much less bear the thought of losing you. You have been as dear to me as anyone in this world.

“I shall hope against hope that you may weather this misery, and be restored again to the joy of full living. But if this is not to be, I must thank you—thank you, once again, and for the last time, for living—for being you—and bid you a final farewell in this life. God bless you; And if your time has come, receive you into the Long Home where there is no more parting.”

Michael used to sing Ain’t No Sunshine about me when we had to be parted. Now I sing it about him … until we can be reunited in the Long Home.

Ain’t No Sunshine

by Bill Withers

Ain’t no sunshine when she’s gone

It’s not warm when she’s away

Ain’t no sunshine when she’s gone

And she’s always gone too long

Anytime she goes away

Wonder this time where she’s gone

Wonder if she’s gonna stay

Ain’t no sunshine when she’s gone

And this house just ain’t no home

Anytime she goes away

And I know, I know, I know, I know

I know, I know, I know, I know

I know, I know, I know, I know

I know, I know, I know, I know

I know, I know, I know, I know

I know, I know, I know, I know

I know, I know

Hey, I ought to leave the young thing alone

But ain’t no sunshine when she’s gone

Ain’t no sunshine when she’s gone

Only darkness every day

Ain’t no sunshine when she’s gone

And this house just ain’t no home

Anytime she goes away

Anytime she goes away

Anytime she goes away

Anytime she goes away

One Art

by Elizabeth Bishop

The art of losing isn’t hard to master;

so many things seem filled with the intent

to be lost that their loss is no disaster.

Lose something every day. Accept the fluster

of lost door keys, the hour badly spent.

The art of losing isn’t hard to master.

Then practice losing farther, losing faster:

places, and names, and where it was you meant

to travel. None of these will bring disaster.

I lost my mother’s watch. And look! my last, or

next-to-last, of three loved houses went.

The art of losing isn’t hard to master.

I lost two cities, lovely ones. And, vaster,

some realms I owned, two rivers, a continent.

I miss them, but it wasn’t a disaster.

—Even losing you (the joking voice, a gesture

I love) I shan’t have lied. It’s evident

the art of losing’s not too hard to master

though it may look like (Write it!) like disaster.

© Margaret Anna Alice, LLC

☕️ Can You Spare 1 Coffee a Month?

I’ve lost 115 paid subscribers since January, and it would be a lot more than that if so many of you hadn’t stepped up to support me while others understandably tightened their belts in this imploding economy.

I want to thank the 1.59 percent of you who pay for a subscription 🙏 To the remaining 98.41 percent, please consider subscribing. I have lost thousands of dollars’ worth of income, and Substack is how I feed our fourteen kitties and myself.

Will you help me by subscribing or making a one-time donation?

You may not think your few dollars a month makes much of a difference, but every dollar absolutely helps—not only financially but also emotionally as it shows you feel my content is worth supporting.

When you subscribe, you gain access to premium content like Memes by Themes, podcasts, Consequential Quotes, Case in Point, Behind the Scenes, Dissident Dialogues in progress (“rolling”), personal writings, and bonus articles.

😇 If you take the extraordinary step of becoming a Founding Member, you will enjoy benefits such as:

signed & personalized copy of Canary in a COVID World

special gifts

select typeset PDFs

Zoom call

I especially want to thank those of you who have taken the time to write a private message to me when you subscribe. I read and cherish each note.

Thank you for being part of our karass of brave, brilliant, kind, and witty thinkers.

🤲 One-Time Support

🌟 New Premium Content

🙏 Shoutouts Gratitude

🛒 Spread the Words

If you would like to help propagate the message that Mistakes Were NOT Made, you will find a wide selection of products in this collection.

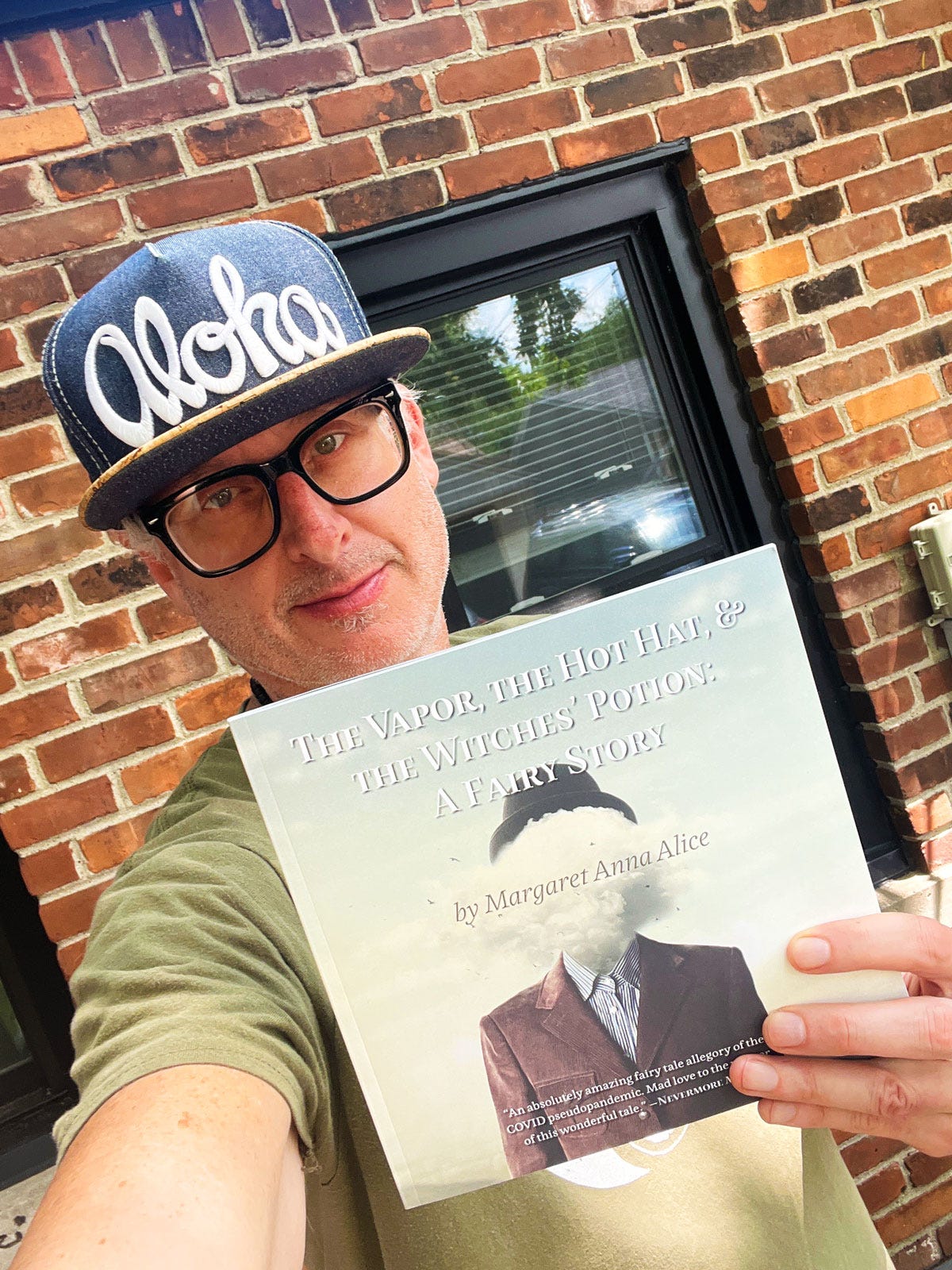

📖 Get Signed Copies of My Book

The holidays will be here in a flash, so now is the time to stock up on signed, personalized copies of my fairy tale for your loved ones. It makes for a thought-provoking, accessible gift whether they are awake or asleep, adults or children.

📚 Anthologies

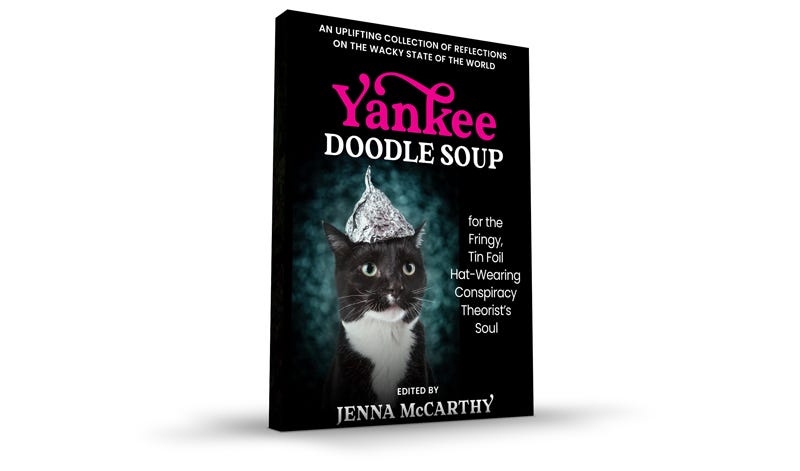

Yankee Doodle Soup for the Fringy, Tin Foil Hat–Wearing Conspiracy Theorist’s Soul

Edited by Jenna McCarthy, this hilarious anthology includes Letter to a Mainstream Straddler and Letter to Klaus Schwab. The paperback is only available for purchase at her website. If you enter the code ALICE at checkout, Jenna will give me a royalty 🙏

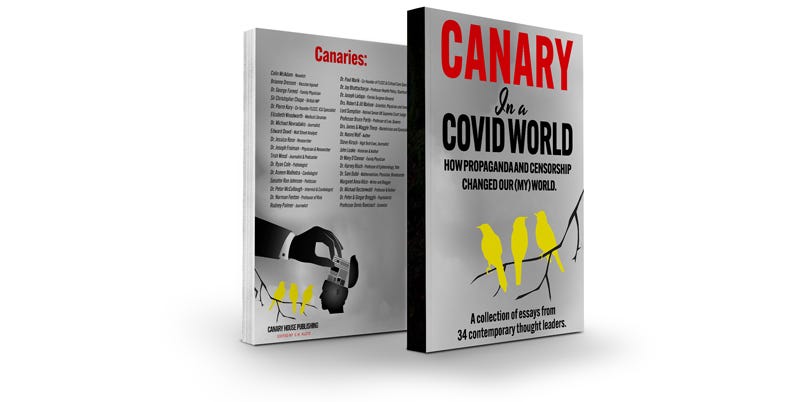

Canary in a (Post) COVID World: Money, Fear, & Power (Hardback, Paperback, Kindle)

The second volume in the Canary series just dropped, and I am grateful to be a contributing author once again.

Canary in a COVID World: How Propaganda & Censorship Changed Our (My) World (Paperback, Kindle, Audiobook)

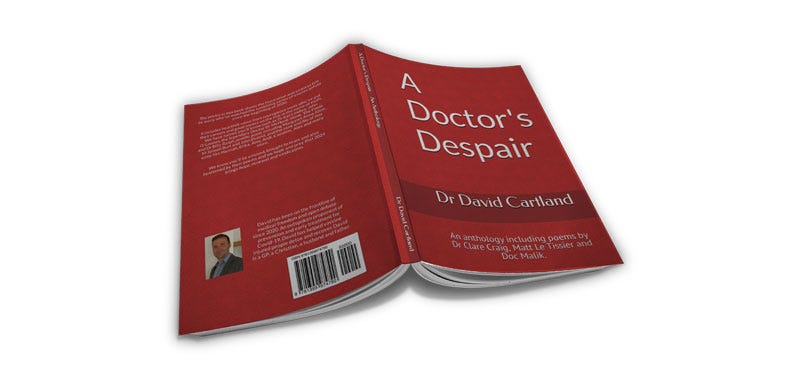

A Doctor’s Despair (Paperback, Kindle)

🐇 Follow Me on Social Media

⏰ Wake-up Toolkit

My Wake-up Toolkit is a great way to get acquainted with my content. I’ve organized my articles by topic for easy reference and use in your red-pilling efforts as needed. Note that I have not been able to update this since June 2024 due to a technical issue, so check my archive for more recent additions.

🌟 WARM GRATITUDE FOR THE RECS!

The single-most important driver for new readers joining my mailing list is Substack Recommendations. I want to thank every one of you who feels enthusiastic enough about my Substack to recommend it, and I especially appreciate those of you who go the extra mile to write a blurb!

Remember, a subscription to Margaret Anna Alice Through the Looking Glass makes for an intellectually adventurous gift down the rabbit-hole!

Note: Purchasing any items using Amazon affiliate links included in my content will further support my efforts to unmask tyranny.

Michael dubbed Dr. Oliver Sacks “The Cherub” after we first read The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat around thirty years ago. He is my favorite nonfiction author and has been beloved in our household ever since as I shared in this 2022 post and this one published on my three-year Substack anniversary.

Share this post